Self-Help Enterprises

Self-Help Enterprises (SHE) is a community development organization located in Visalia, California, whose mission is to work together with low-income families in the Central Valley to build and sustain healthy homes and communities. We worked specifically with their Emergency Services team, who collect and use data sourced from domestic well assessments at private properties. They use these data to identify issues related to water contamination and water access and determine who might be in need of resources such as interim water access, well replacement, or filtration systems. While this is SHE’s primary data usage, they also use the data to understand more about the groundwater supply and contamination levels in order to predict how households will be affected by agriculture and natural disasters, such as severe drought. Water supplied by most domestic wells is not regulated by government agencies in California, so the data being collected is critical for current and future planning.

Groundwater Contamination and Depletion in the San Joaquin Valley

SHE’s service area spans across nine counties that are located in the San Joaquin Valley, one of the most productive agricultural areas in the world. This level of agricultural productivity has played a role in both depleting and contaminating the groundwater supply. Chronic overpumping of groundwater has resulted in dry wells and threatens long-term reserves.[1] Excess manure and fertilizer runoff adversely affect the quality of the groundwater that remains, causing algae blooms and contaminating well systems with nitrates, arsenic, coliform bacteria, pesticides and disinfectant byproducts.[2]

Nitrates are the most prevalent chemical found; “one in every 10 water samples collected from 20,000 wells in the Tulare Lake Basin and the Salinas Valley exceeded the drinking water standard for nitrate in 2012.”[3] Exposure to nitrates over long periods of time can lead to dangerous health conditions, including serious reproductive health issues and many types of cancers.[4]

Self-Help Enterprises collects…

SHE collects, uses, and manages many different types of data, including:

- Water quality data from wells during site assessments

- Standing water level (depth to groundwater) data and well depth from wells during site assessments, measured at a specific point in time

- Real time groundwater levels post-new well drilling

- Isotope testing to track the levels and movement of contamination

.png)

Challenges

Self-Help Enterprises described several challenges surrounding the #usage, sharing, and general governance of these data. They feel that there is a disconnect between government and private homeowners: homeowners don’t want their water usage being monitored by the government, yet the data that is being collected to understand the environmental conditions of communities can inform policy and funding decisions. SHE acts as a middleman, with the goal of using this data to provide services to community members and share data in a protected and controlled manner with relevant government agencies. By utilizing safe data sharing practices, SHE’s goal is to build #trust between their organization and the communities they serve, while supporting government agencies in building trust with constituents themselves.

As a part of funding agreements with government agencies, SHE has to share certain categories of domestic well data with various entities, including government agencies and partner organizations, while maintaining the privacy and confidentiality of domestic well users. Funding agencies also require synthesized and sometimes, raw data sharing as part of the reporting requirements outlined in funding agreements. The funder uses the data both to monitor performance and to understand environmental conditions in the community and inform policy and funding decisions. SHE typically shares aggregated data with partners such as community-based organizations (CBOs) and local government agencies in the context of collaborative working groups and task forces to support shared goals of public health and safety (this is not necessarily a requirement, but an expectation given their role in the domestic well space). SHE co-owns this data with the property owners, and they want to build out policies that standardize what #dataco-ownership looks like in principle and practice.

The team at SHE is committed to “doing good” with the co-owned data; they understand that once data leaves their hands, there is almost no way of knowing how that data is going to be used. With this understanding, they do want to share data with the broader community and region in a manner that is representative of the issues and supports advancing solutions, while protecting the individuals and communities that they work with from undue risk. Examples of risks to low-income families and communities include: depreciated home and neighborhood values, tenant displacement, reduced affordable housing, stock condemnation, and code violations. SHE has team members with extensive expertise in creating #dataproducts that de-identify or obfuscate the data, and the team wants to create heat maps that buffer individual data values into aggregated representations. They want to both act responsibly with their co-owned data and also contribute to larger scientific and research efforts. SHE has contributed to water quality and water level data collection for research projects and local planning projects on behalf of universities and local water districts. Regarding training, SHE’s water quality staff undergo training through the Water Quality Association for credentialing. Because of the uniqueness of their programs, much of the standards and protocols for our data #collection and program implementation have been developed in-house.

Current governance and management

The SHE team is large—over sixty staff members are involved with managing data in some way. Currently, the data is not publicly available, but program participants can see the data collected from their own site assessments. SHE is planning to create aggregated data products in the future, but currently, there aren’t any available. There are several organizations that they share water quality and well level data with, including the California State Water Resources Control Board, as a condition of funding. They also share with the California Department of Water Resources, to report when a domestic well goes dry, or when it is repaired or replaced, as a part of the Dry Well Reporting System. In the past, they have shared data with universities conducting #research on drought in the San Joaquin Valley.

Goals

SHE isolated an overarching objective for our collaboration: explore data governance topics related to the policies and procedures of building a water quality data access and storage system. They wanted to accomplish three main goals within that objective:

- strengthen agreements with participants about data sharing,

- create language about “How We Share Data” and SHE’s core data practices, and

- leave the workshop with a clear understanding and policy direction on data use and desired data products.

The team chose these goals with some long-term outcomes in mind, including stewarding a dataset that can be shared statewide and managed responsibly in order to prepare for disasters and protect the most vulnerable populations. The team viewed this work as a preparedness effort and a community risk prevention effort. Ultimately, they also wanted to be able to save community members from risky situations by recommending areas where it’s not sustainable to build houses.

In the workshop

We designed the workshop to cover three modules: 1) creating foundational documents to support organizational culture for data sharing, 2) a data sharing agreement building exercise, and 3) supporting data products. We had a half-day in-person workshop to run through these modules, in which twelve members of the SHE team participated.

Module One: Creating foundational documents to support organizational culture for data sharing

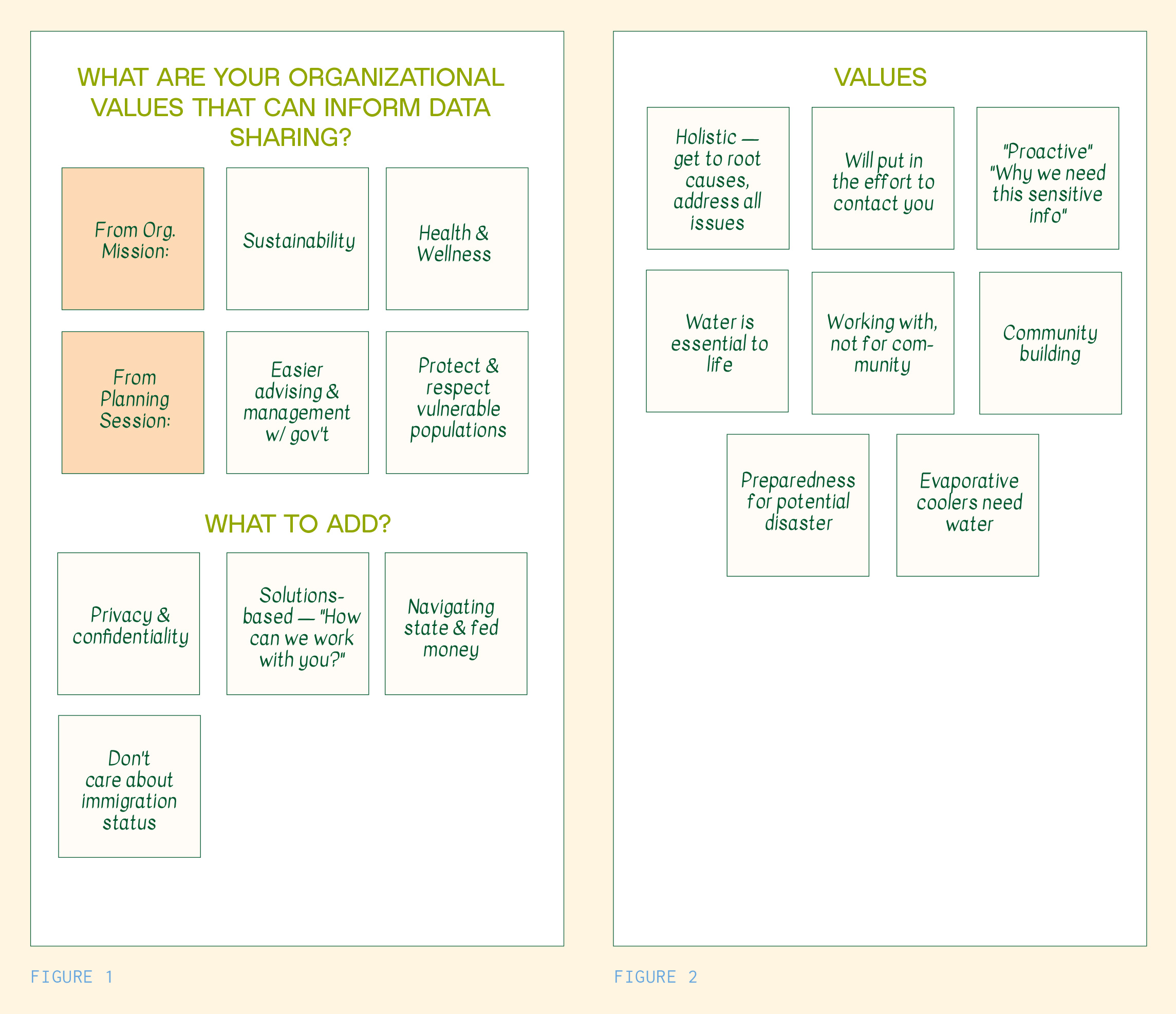

The first module reflected SHE’s need to create organizational language related to its values and practices on how it shares data. This language could be referenced in the future when entering into partnership with a new data sharing party, collecting a new type of data, or creating a new tool or policy. We facilitated a conversation that brainstormed and surfaced the team’s values on data usage and sharing, with the goal of setting up a “How We Share Data” document for internal and external use. We pulled together organizational values from their mission and the planning session, and asked participants to add other aspects from their established workflows and organizational working culture. See Figures 1 and 2, below, for the notes we documented from the session.

The team generated a robust list of values that are derived from their practices and that actively inform their approach to their work. Some of the values reflected their overall ethos and understanding of what their region experiences in their environment, with participants underscoring the maxim that water is essential to life, and that they try to get to root causes to address multiple issues, rather than just treat the symptoms of a problem. These values reflected the team’s positionality as a trusted liaison between communities, and government agencies, and how they navigated these relationships with deliberation and care.

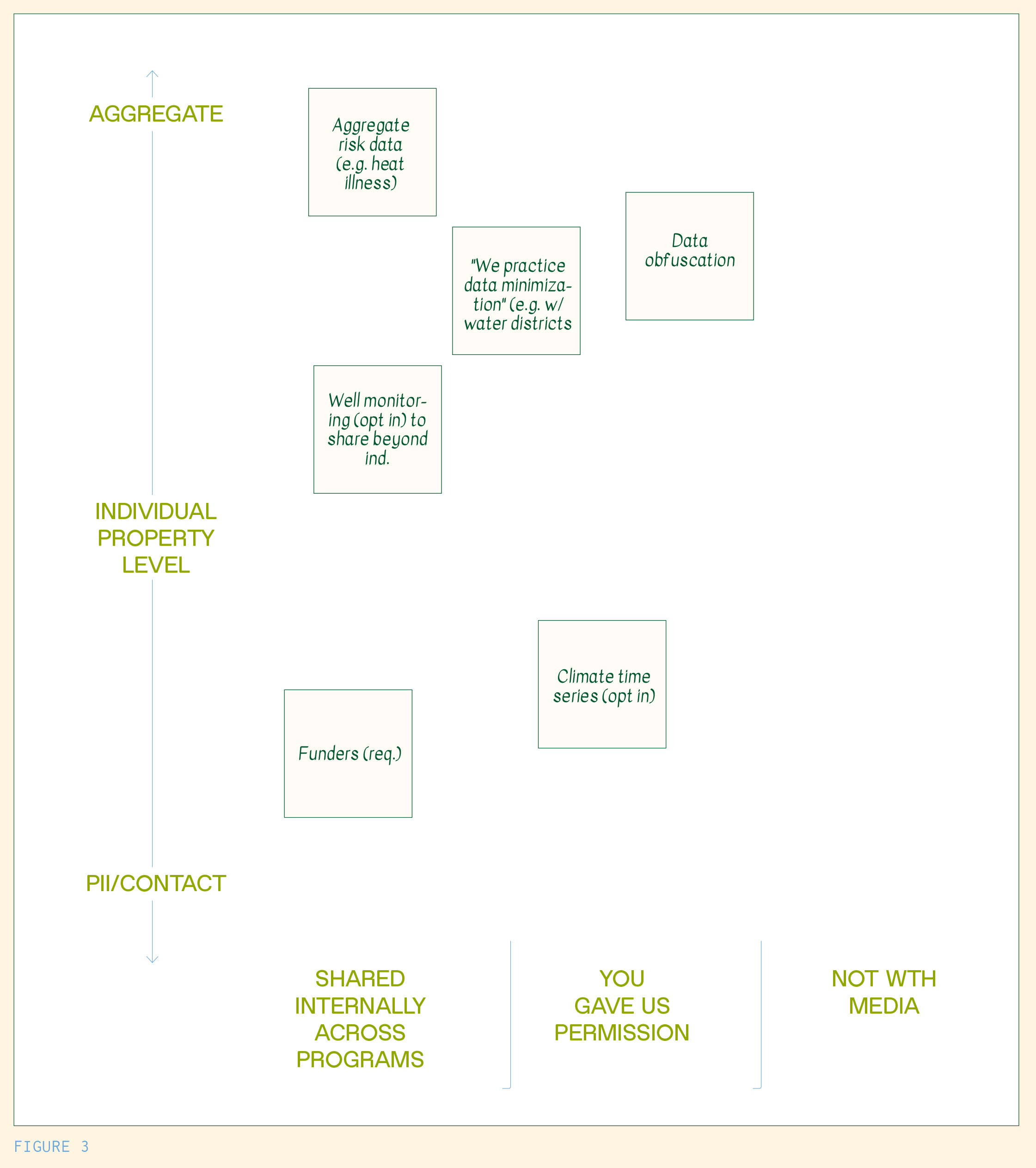

Building on those values, we posed two additional questions for their How We Share Data document: 1) How does data sharing support your mission and program efforts? and 2) How do you plan to use the data? Opening this up to discussion, a response to the first question was clear: data sharing supports connecting participants to resources (i.e., interim water access, and technical and funding assistance), which supports the protection of water, which is essential to life. In discussing the second question, the team delineated how they would use data based on a spectrum of data types, from Personal Identifiable Information (PII) and contact information, to individual and property level data, to aggregated forms of data.[5] See Figure 3 for this spectrum. This allowed the team to understand and articulate current and future data uses.

For a more detailed exploration of building a data values statement with your team, see our template: Data Values Statement Template, and the accompanying how-to guide: Our Data, Our Values — A How-To Guide for Creating Data Values Statements.

Takeaway 1: Data values statements are vital to create a basis for decision-making and team cohesion.

Values are the foundation for collaboration, and data governance relies on collaboration, both internally and externally. Our work with SHE once again demonstrated this, and creating a data values statement, like a “Why and How We Share Data” document is one way to establish a formal recognition of these values. Just as an organization’s mission and vision guide their purpose and align the team’s actions, a set of data use values can provide a strategic direction for an organization that relies on using and sharing data to fulfill its goals. Internally, it creates a baseline for how to create data workflows, products, and infrastructures; externally, it sets expectations of others and serves as a guide to organizational commitments.

A data values statement can serve as an explicit call to bring ethics into organizational practices and programs that may otherwise not see the connection between their activities, data, and goals. The team at SHE recognizes the value of their data, both to execute their mission and serve their program participants; it also wants to send a signal to bad actors who seek to use this important information to serve their own purposes at the expense of communities. Data values statements, when instrumentalized by legal and technical protections, can draw a line that demarcates who can and will benefit from this data, what will be done with it, and how it will be managed throughout the data lifecycle.

Module Two: Building a data co-ownership agreement

In the second module, we focused on building out a data co-ownership agreement template to bolster current workflows at SHE. The Emergency Services team’s participation agreement does not currently include any questions related to data sharing. As such, the goal of this session was to draft 1) the structure of a data co-ownership document for participants in the well site monitoring program, and 2) create a list of considerations for data sharing for another program of their choosing.

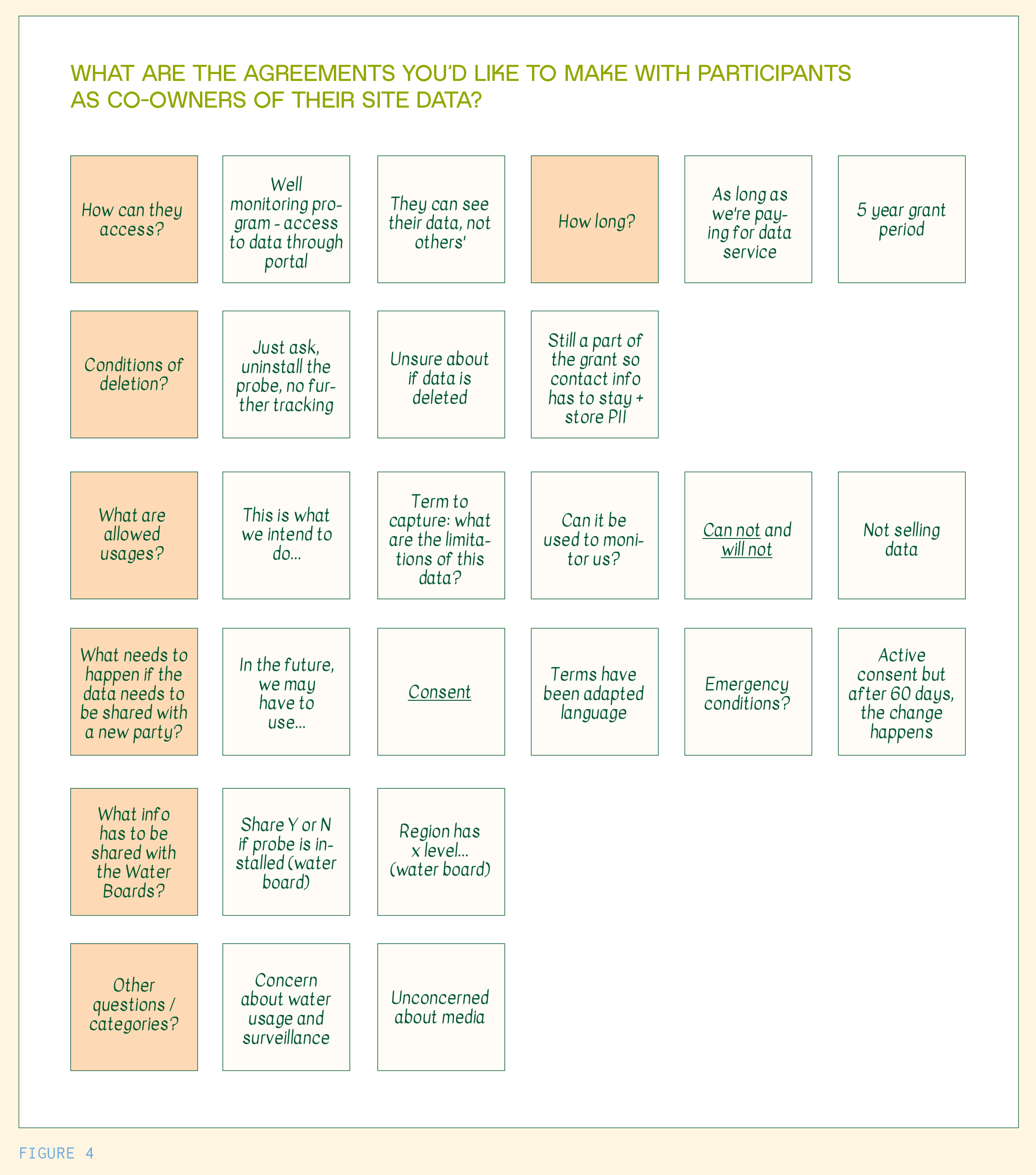

We opened the discussion by asking team members about the agreements they’d like to make with participants as co-owners of their site data, and we posed questions to spark ideation. These questions are listed below, in Figure 4, and include queries about access, condition of deletion, sharing, and usage. This conversation highlighted what the team valued most in collaborations with program participants, including consent and transparency. For example, there are certain reporting requirements imposed by agencies and funders that the team feels participants need to know up front.

To view and utilize a data co-ownership agreement template, see our tool: Data Co-Ownership Template and the accompanying co-ownership how-to guide: Our Data, Our Rules — A How-To Guide for Environmental Data Co-Ownership.

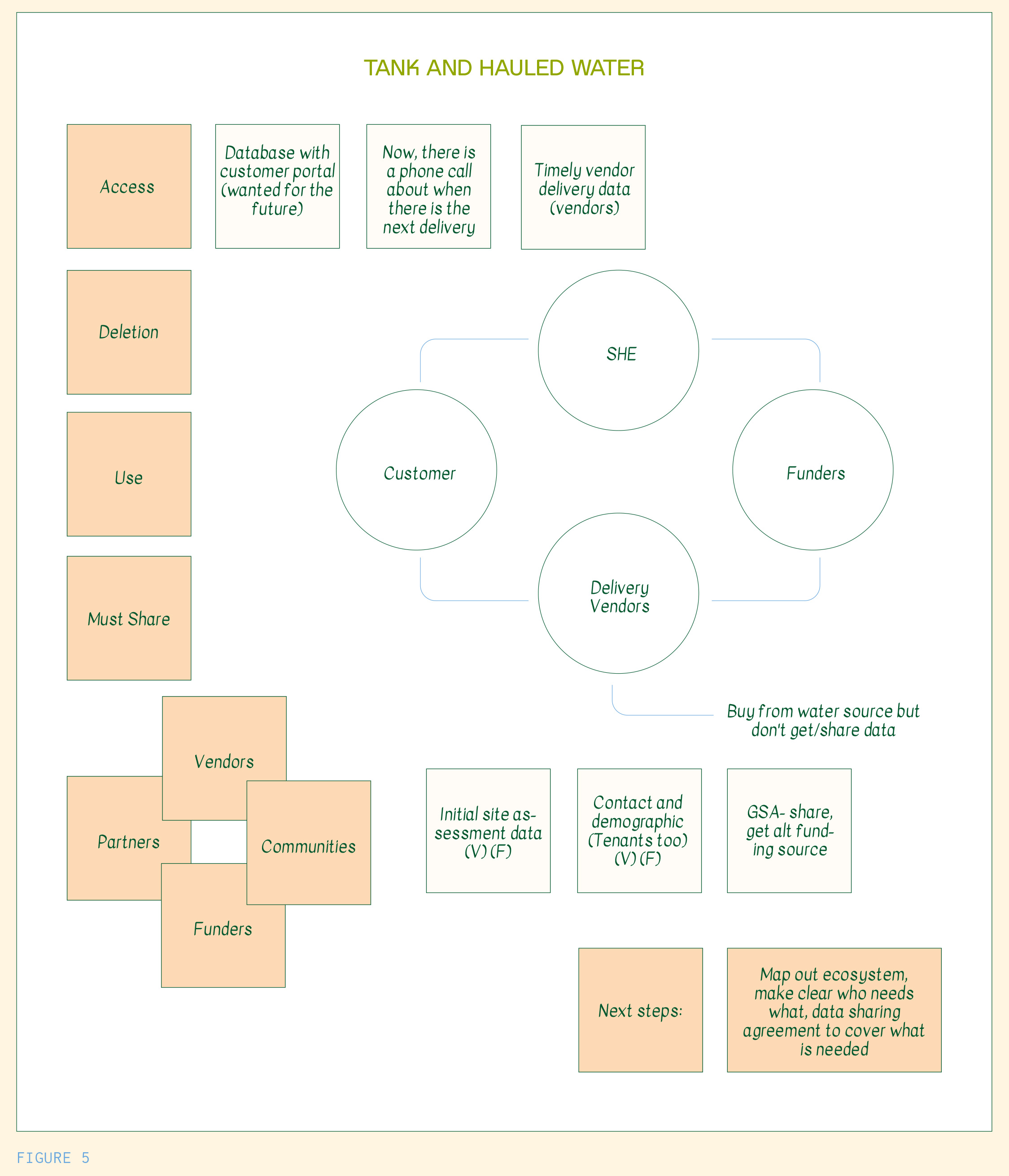

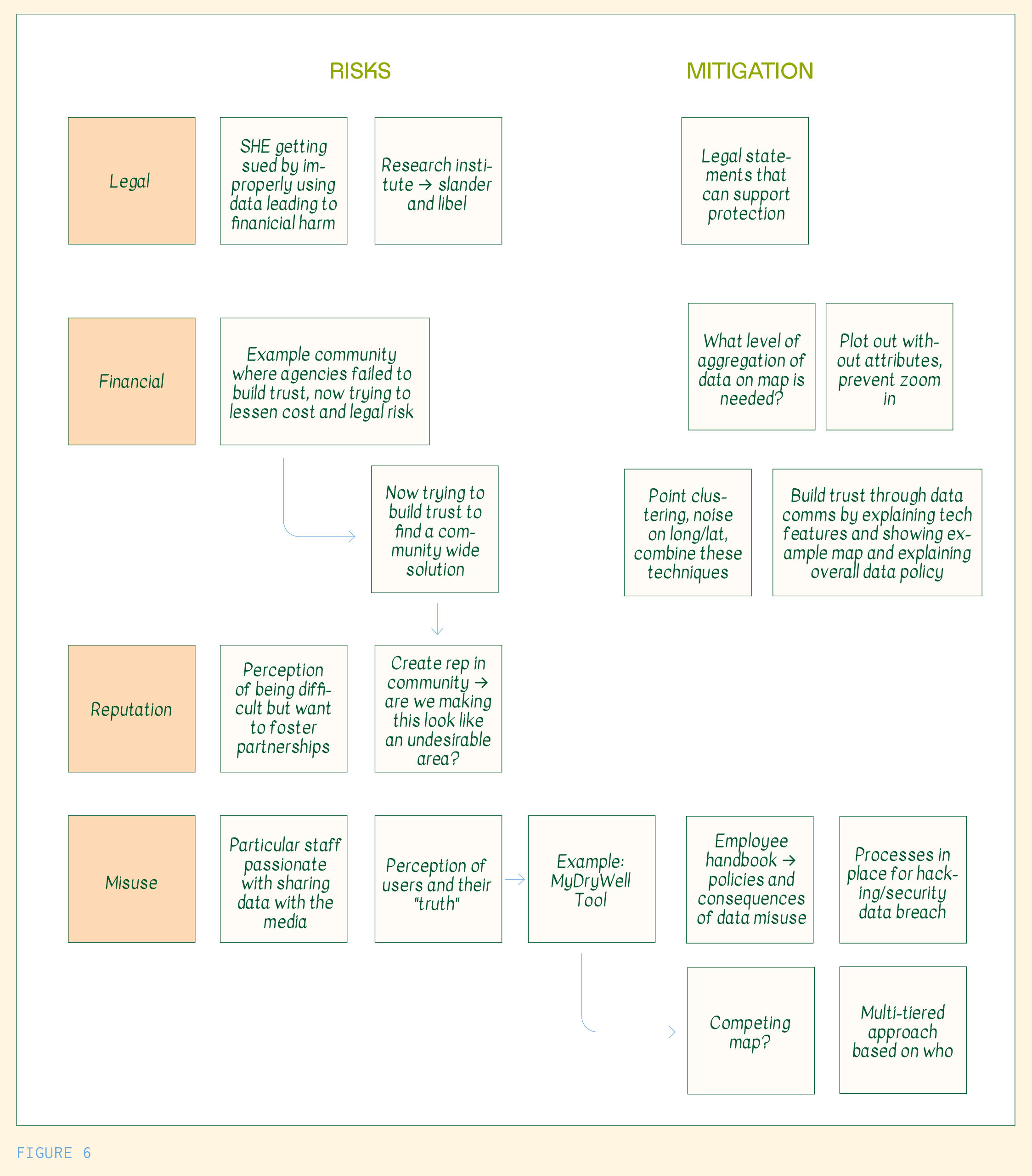

We then analyzed data sharing considerations for SHE’s Tank and Hauled Water Program. This program temporarily supplies water to participants whose wells are dry. We mapped the general flow of data and information shared between participants, delivery vendors, funders, and SHE. We diagrammed a detailed data ecosystem, and, after the workshop, formalized the ecosystem graphically, including possibilities for how and where a customer portal could be used to support two-way data exchange. We also listed questions and considerations for each stakeholder, including discussion topics for contracts, data sharing, and funding agreements. Notes from this work are documented below, in Figure 5 and 6.

This data ecosystem and accompanying information can be found as Self-Help Enterprises Hauled Water Data Mapping in the Tools and Templates folder.

Takeaway 2: A strong connection between social, legal, and technical components is key to cohesive data governance.

Oftentimes, environmental data are collected, used, and managed without accounting for the entire data lifecycle and the corresponding technical, legal, and social infrastructures. Organizations may have a stellar technical database, but the management policies and legal infrastructures could be lacking, or vice versa. In the case of SHE, the team has set up a robust technical infrastructure where data is safely held, but has yet to build out a larger data governance framework for legal mechanisms for sharing (e.g., data sharing or ownership agreements). They have certain policies for understanding if participants want their data to be shared with media, but lack policies detailing other explicit permissions and uses of the data.

This presents an opportunity to build out the formal data governance framework for their organization using the resources we co-designed in the workshop. SHE could further codify their current workflows, detail internal permissions and roles in data #management, and solidify sharing processes. The social, legal, and technical components could be designed to reinforce one another and systematically serve the ultimate goals of the data #collection and #usage.

Module Three: Supporting data products

The third and final module focused on #dataproducts and #risk. SHE is in the process of creating a data repository for data from site well assessments. They are currently working to anonymize and de-identify the data, but also want to create products that aggregate the data.

The team identified several data products that they’d like to create, including dashboards of water delivery schedules and programmatic milestones for program participants, ArcGIS maps with water access and water quality layers, and heatmaps that give information on dry wells at a neighborhood-level. These kinds of products would be beneficial to participants within the community and, potentially, other communities within the broader Central Valley.

One product in particular would feed the well information into a database and generate customized, property-level reports on water quality and quantity, as well as environmental risk. Different types of risk can be associated with this data product, including legal, financial, reputational, and misinterpretation risks. Based on identified risks, we brainstormed potential mitigation measures through technical design or other approaches. Our aim was not to scare the team by presenting all potential risks, but to build the muscle of recognizing risk and factoring in mitigation methods as data products are created, not afterwards.

The risk-related themes that emerged were largely related to reputation and misuse: Self-Help Enterprises wants to uphold its long-held reputation as a trusted partner that works with communities to find solutions on issues, spanning from water to housing. Their work relies on that trust and those relationships. #Misuse was also an area of heightened potential for risk, especially related to press coverage and research partnerships; these stakeholders don’t have the same social bonds with the communities, and aren’t accountable to them in the ways Self-Help Enterprises is. Several mitigation strategies were identified, ranging from legal statements and contracts to technical workarounds that obfuscate data and internal policy changes that address data misuse and security breaches.

Takeaway 3: Risk exists, but deliberately designed data governance can create pathways for opening up data in responsible ways.

There is a common phrase in data governance that one can create a governance framework where data is “as open as possible and as closed as necessary.”[6] At OEDP, we see openness as a spectrum, and that the binary of open/closed data does not respect the nuance of many environmental data uses and contexts. SHE recognizes the need to protect their program participants while also using this data to advance both immediate services as well as strategic and holistic solutions for the Central Valley that address the root causes of water scarcity and contamination.

Resources created, next steps, and outcomes

After the workshop, we created a set of templates to support SHE’s data governance work moving forward. The templates included a data values statement (i.e., a document describing why and how SHE shares data) and a data co-ownership document to share with participants. We also shared a workbook featuring a diagram of the hauled water program and data questions and considerations for each stakeholder, such as discussion topics for contracts and data sharing and funding agreements. These resources are linked above and available in the Tools and Templates folder.

With each community partner, we held check-ins at the three and six month marks after our official collaboration ended. These check-ins were designed to report on progress and discuss emergent questions. SHE reported that they will be integrating their data values statement into their organization’s five-year strategic planning in 2025, and they are interested in developing a broader strategy for data governance across the organization during the upcoming strategic planning process, as well. They also reported some emerging ideas regarding integrating climate change data into their work as affordable housing developers.

https://www.ppic.org/publication/water-use-in-californias-agriculture/ ↩︎

https://nationalpartnership.org/report/clean-water-case-study-san-joaquin-valley/ ↩︎

https://calmatters.org/environment/2023/04/california-floods-contaminate-water-nitrate/ ↩︎

https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/public_notices/petitions/water_quality/docs/a2239/overview/Documents/AR-Docs (296).pdf ↩︎

Personal Identifiable Information (PII) are data that can be used to identify individuals, and might include someone’s personal address or phone number. Individual and property level data in this instance include the data collected related to well amounts or contamination. Aggregated forms of data include maps, charts, or other data products that are made up of individual data, but that data cannot be assigned to specific properties or individuals. ↩︎