CoAct

CoAct is a project team that includes El Centro de Investigaciones para la Transformación, or the Research Centre for Transformation, at the National University of San Martin (CENIT) and Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), or Environment and Natural Resources Foundation, in English. Together, they created and now actively maintain the social citizen science tool ¿Qué pasa, Riachuelo? (QPR). This tool collects and displays data on #waterquality, as well as the uses and perceptions of natural areas in the Matanza-Riachuelo basin. CoAct uses participatory research and citizen social science practices[1] to integrate these stakeholders into the project at different stages, whether during design or result interpretation.[2] CENIT and FARN aim to promote synergies between scientists and academic researchers working in the basin, communities and organizations interested in environmental education, and decision makers in the region. The research group investigates three key themes: natural areas, relocation and redevelopment, and water quality.

Contamination in the Matanza-Riachuelo Basin

CoAct’s collaborative #mapping platform covers the Matanza-Riachuelo Basin, a 40-mile long river and its surrounding areas, where six million people, approximately 15% of the Argentinian population, live.[3] This river and its surroundings are heavily contaminated by multiple and diverse sources, including industrial waste, sewage effluents, open garbage dumps, and organic run-off from meat packing plants. Sewage effluents are especially common since 50% of the population in the basin is not connected to the sewage system. People near the river suffer from health issues, including severe skin rashes, vomiting, diarrhea, and headaches, as well as lead poisoning and high cancer rates.[4][5]

The contamination became so severe that in 2008, Argentina’s Supreme Court declared the river an imminent threat to those living near the water and ordered the rehabilitation and sanitation of the entire basin. A governmental authority called Matanza-Riachuelo Basin Authority (ACUMAR) was established by law in 2006 to lead the environmental and social recomposition of the river basin; this included river clean up, in addition to creating housing projects and improving the population’s access to potable water, sewage services, and health care.[6] While there have been some improvements—namely installing new sewage systems, clearing garbage from the river, and shutting down abusive factories[7]—ACUMAR still struggles with appropriately allocating funds and government capacity to address some of the root causes and create holistic solutions on a basin-wide level.[8] For example, the public information system is often considered insufficient in relaying project-level updates to the public, although it has published reports about policy implementation and regularly made datasets public in the past. Additionally, biologists have pointed out that some of ACUMAR’s superficial changes, like shoreline parks and public spaces, distract from the larger ecological crisis basin-wide.[9] ACUMAR is understandably overburdened regarding capacity: the authority has to address and manage interjurisdictional struggles amongst three levels of government - 14 local governments, 2 state governments, and the federal level authorities. Currently, many are concerned about continued funding considering Argentinian president Javier Milei’s approach to cutting what he considers “non-essential spending.”[10] Moreover, at the end of 2024, the Supreme Court abandoned the supervision of the sanitation plan.[11]

CoAct Collects...

The CoAct project collects observational water quality data and data about natural areas' uses and perceptions in order to investigate three key themes: natural areas, resettlement and redevelopment, and water quality.

- Data about natural areas: Wetlands and green spaces are threatened by contamination, industrialization, and urbanization. The QPR platform enables the sharing of information about the biodiversity of those spaces and the threats they face.

- Data about relocation and redevelopment: Relocation and reurbanization processes are a part of ACUMAR plans, and with QPR, communities can monitor different aspects of the process and share their experiences of participation in government programs.[12]

- Data about water quality: QPR facilitates community participation in generating information about observable variables on water quality that complements existing public data. This supports sanitation policy, and allows people to “observe the river, assess its biocultural importance, and monitor variables associated with water quality to support decision-making.”[13]

Challenges

CENIT and FARN described several challenges surrounding the usage, sharing, and general governance of these data during the CoAct project. The team wanted to translate the technicalities of data governance to non-academic stakeholders in the project, including the citizen scientists using the QPR tool and local and regional government decision makers. They were interested in understanding how to create the simplest way of translating the governance framework so that the public could understand and get involved. In this vein, the team was interested in exploring how to reach agreements between stakeholders with different interests or values. Considering that public policy in Argentina has been subject to drastic switches in orientation, CENIT and FARN were also interested in creating data governance structures that would not only have strong decision-making frameworks, but also be flexible enough to withstand changing conditions.[14]

The challenges that CENIT and FARN wanted to explore hit upon the idea that many data governance questions are rooted in the relational aspects of data governance. These relational aspects—the “people” side of a technical tool—include decision making structures, #rolesandpermissions, collaborative processes, data sharing and #usage, and #documentation.

Current governance and management

Currently, CoAct’s data is managed by FARN and stored on Amazon servers. Data is submitted by two different kinds of users: registered and non-registered. When non-registered users submit data, they fill out a structured form with closed-ended questions (i.e., single-choice, multiple-choice, or dichotomous), which does not have to be reviewed by FARN. Registered users submit data using a form that includes open-ended questions and the possibility to share documents, links, and images, in addition to structured questions. These open fields are reviewed by FARN (with potential collaboration from the CoAct coordinating team) to check that the content is aligned with the platform’s policy for conditions of use. When reports reach a threshold amount, they are downloaded through the platform’s dashboard, curated by the CoAct team to ensure that files are accessible, and uploaded to Zenodo with a CC-BY-SA license. [15] CoAct’s Zenodo also hosts the metadata and more detailed information on the metadata, tutorials on how to upload open and sensitive data, and the datasets themselves are available for download.

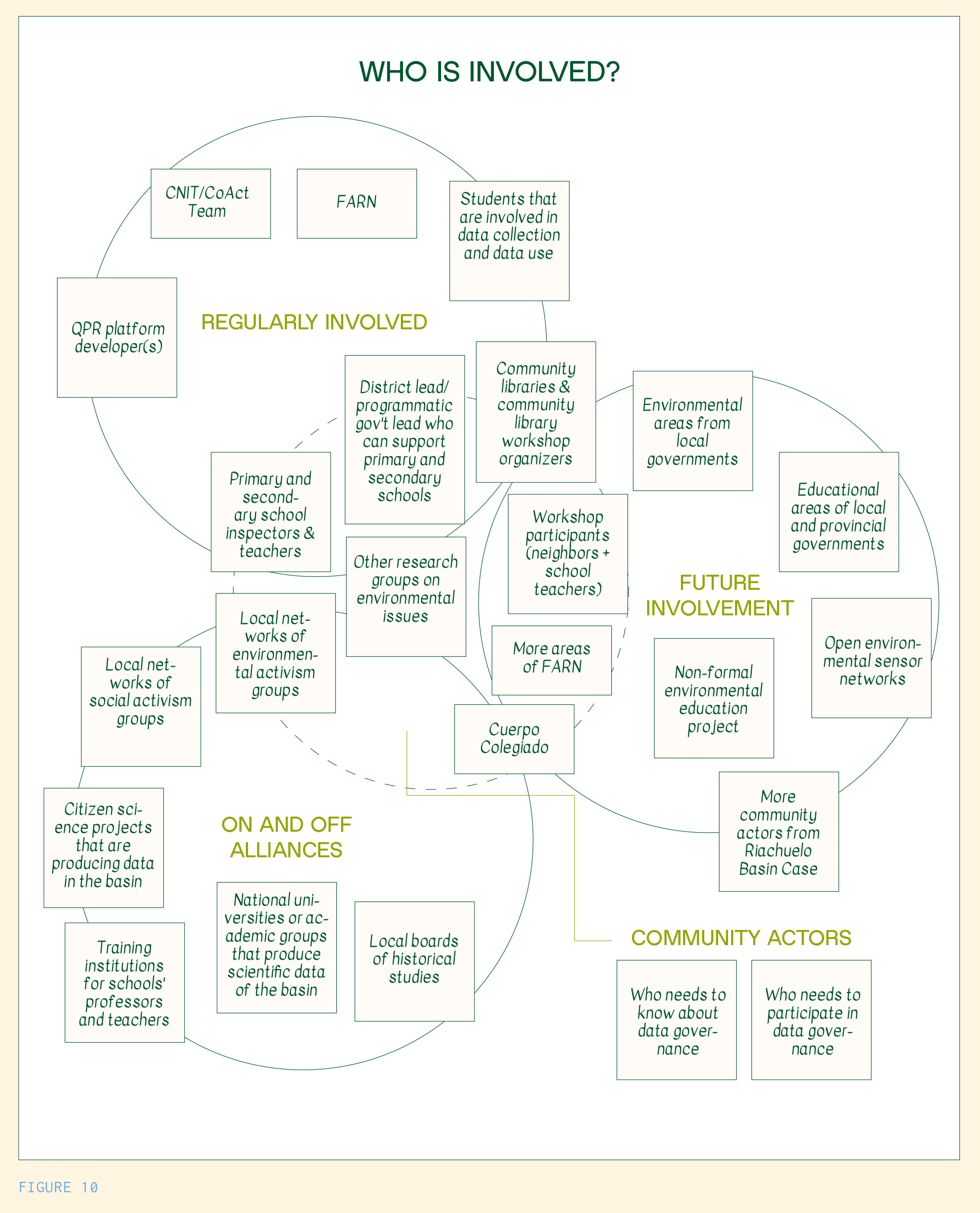

As for social governance, there are many groups currently involved in the project, including CENIT, FARN, and community library workshop organizers and work participants, neighbors, and school teachers. They also have occasional alliances with training institutions for school professors and teachers, local boards of historical studies, and local networks of environmental activism groups. As the coordinating institutions of the CoAct project, CENIT and FARN currently make the decisions, but they hope to extend decision making power to the biodiversity department[16] of FARN and the library workshop coordinators. Decisions are made during bimonthly meetings with the CENIT team and representatives from FARN, using Slack to track issues and GitHub to document advances in the interim.

Goals

CoAct’s main objective was to involve more people in the project and design pathways to increase engagement, whether it be basic awareness, participation in curation, or even stewardship of the data. There were three main goals within this objective:

- Create a plain language data governance framework that could be shared with community actors,

- Develop guidance for community actors to support their involvement in curation and stewardship of the data, and

- Understand and apply methods to increase the diversity of participants.

These goals fed into longer term outcomes, which included increasing the number and diversity of people who are invested in the project during this time of environmental crisis. CoAct wanted to work toward a model where more community actors, including community libraries, schools, and environmental activists, could play a larger role in collecting and managing the data on the platform.

In the workshop

Our workshop covered two modules: 1) mapping CoACT’s current data governance framework, and 2) opening up data governance engagement pathways. Five participants from the CENIT and FARN teams participated in our three-hour online workshop.

Module One: Mapping CoAct’s current data governance framework

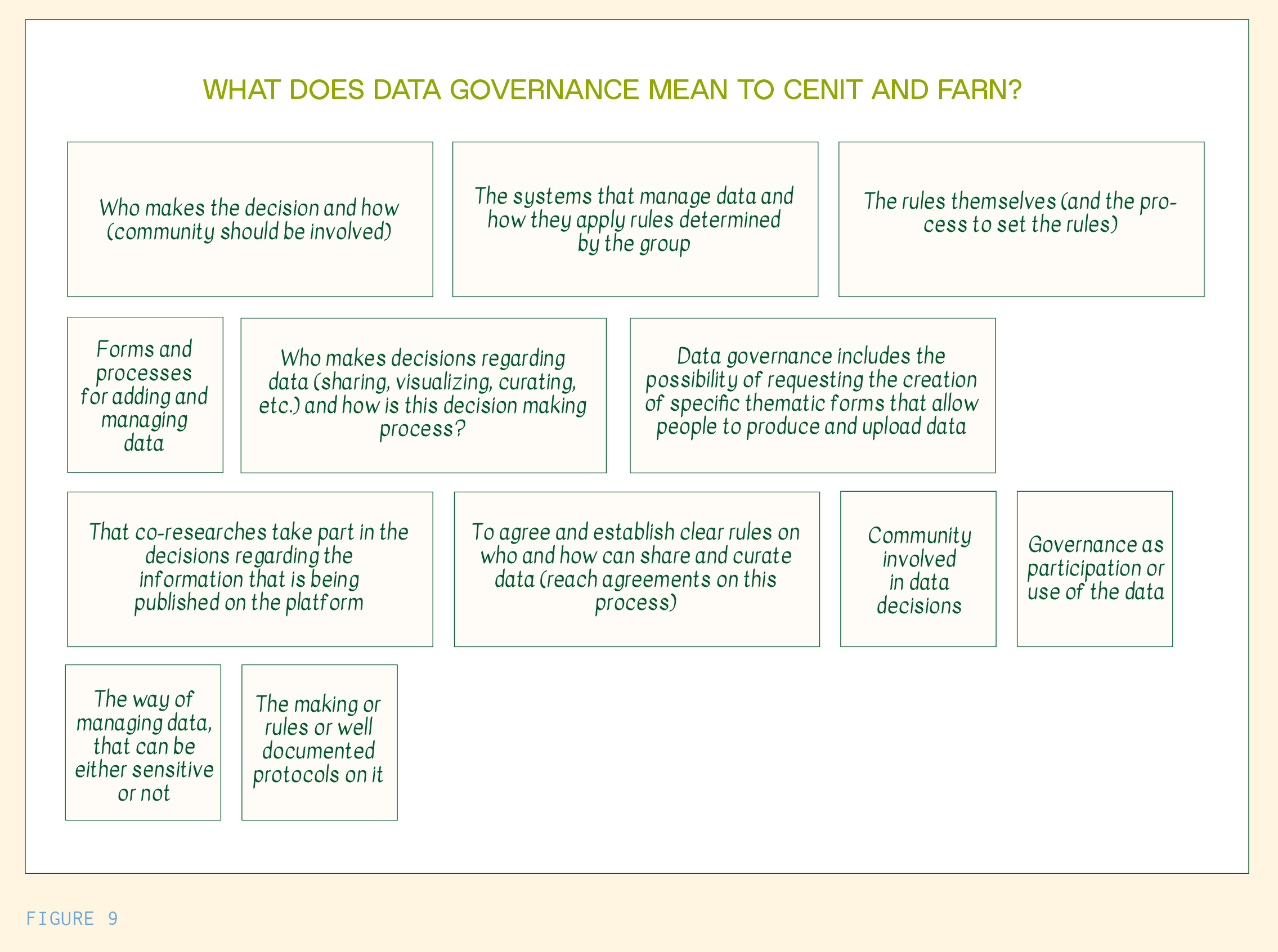

The first module reflected CoAct’s desire to 1) engage with community actors through data governance, and 2) understand in which aspects of governance they might be interested in participating (and how). We focused on how members of CoAct currently understand their governance, who is involved, and which aspects of data governance were a priority for the project. We started this conversation by asking what data governance meant to their project team. Notable responses from the team coalesced around common themes:

- Who makes decisions about data and how

- The importance of community involvement

- Data use rules and the process to set those rules

- Data #management systems and how they apply rules determined by the group

- Forms and processes for adding and managing data

It was evident that a data governance framework for CoAct should explicitly outline decision-making and rule-making processes, the maintenance activities of data management, and how the technical infrastructure could support social and data governance. Most members in attendance had a pivotal role in setting up these rules or systems, but lacked a bird’s-eye view of documentation that could show how the relational and technical pieces come together. This conversation is detailed further below, in Figure 9.

Building on this session, we led a conversation around who was significantly involved in the project, who was involved occasionally, who CoAct might want to bring into the work in the future, and who was considered a community actor. This session surfaced details on the project’s partnerships, and which groups might be prioritized for engagement. An important specification arose during the conversation: CoAct should determine who needed to know about data governance, and who needed to participate in data governance, as this would inform CoAct’s plans to engage them. The CoAct team identified teachers, environmental leaders at the provincial level, and community libraries as the primary actors for participation in governance; meanwhile, educational inspectors or administrators and students might not participate in the governance but should be kept informed of processes. For a comprehensive view of all current and future actors, see Figure 10.

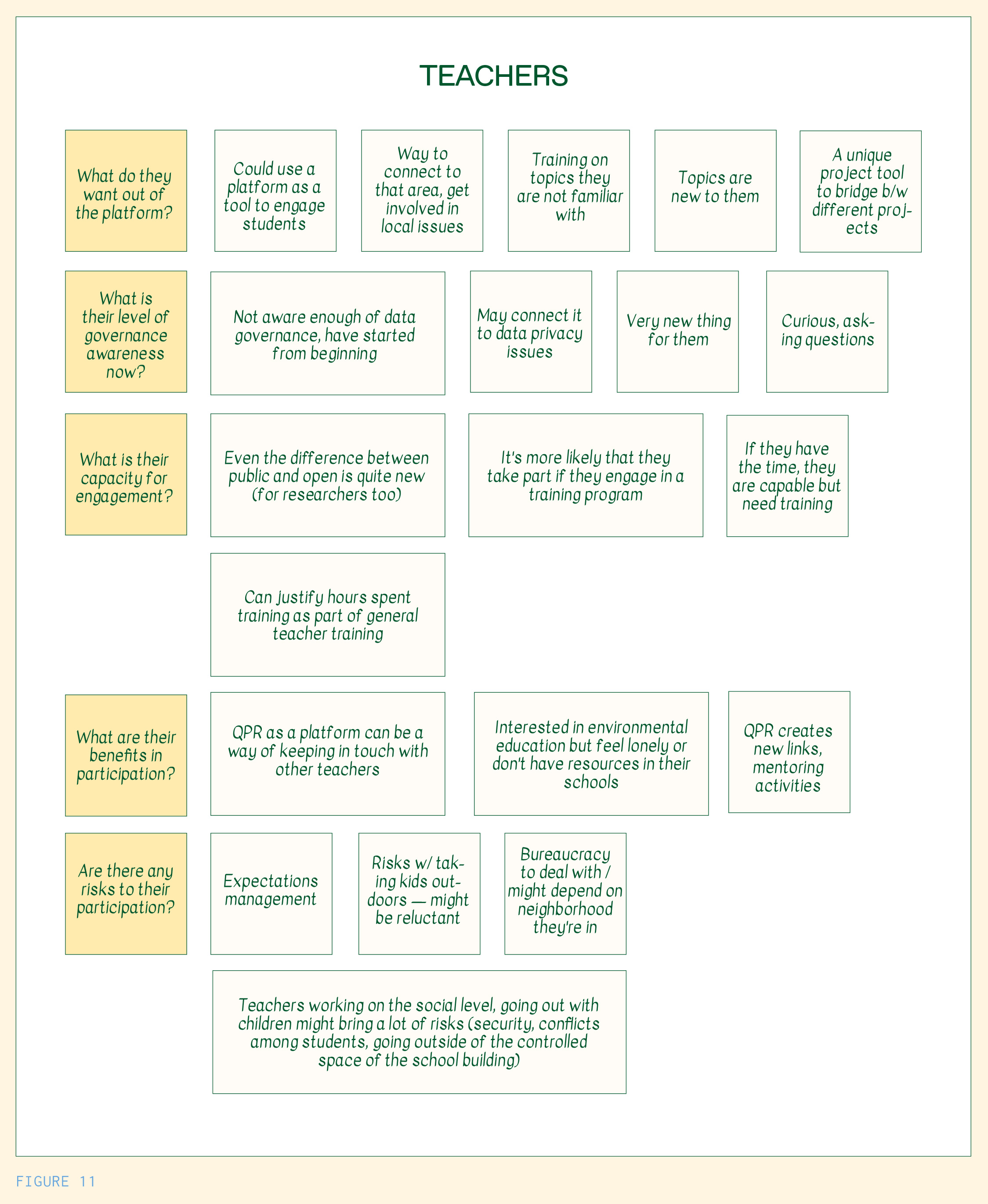

We asked five questions for each priority actor group:

- What are their goals within the project?

- What is their current level of governance awareness?

- What is their #capacity for engagement?

- How would their participation benefit them?

- Are there any risks to their participation?

The answers to these questions painted a fuller picture of each actor to ultimately inform the design of effective engagement strategies. Each of these aspects would influence who, how, and why someone might want to be involved. Furthermore, designing one singular approach to engagement might appeal to one of these actors, but miss the mark for others; it would run the #risk of both giving someone too little information or overwhelming them with too much; or offer benefits that don’t align with an actor’s desires, or involve them in a process that feels risky, either politically or legally. This would be critical in scenarios that are politically fraught, like the current situation in the Matanza-Riachuelo river basin. To see the brainstormed responses for teachers, as an example, see Figure 11.

Takeaway 7: Because data governance can be understood and employed in many different ways, it is essential to define what your data governance framework looks like within your project team.

As facilitators, we hesitated to present a conclusive definition to our partners because data governance, and correspondingly, data governance frameworks,[17] can look differently to different communities and depends on the context and priorities of a project and team. Still, within each community or project, a commonly held understanding can support putting a data governance framework into practice. Data governance is often an emergent topic for communities working with data, who have been utilizing data governance practices or processes, but not yet using this terminology. Defining data governance with a project team can be a simple conversation among those involved. They can begin by asking what each person’s definition or idea of data governance is, and then identifying the commonalities and differences, and piecing together a definition describing the team’s interpretation of the term. This can facilitate the further alignment of priority data governance practices and processes, constituting the beginning of a framework.

Takeaway 8: Documentation underlies effective collaborative data governance and institutional knowledge.

#Documentation is critical to managing environmental data projects where multiple actors are involved in different aspects of the project. Like data documentation, data governance documentation can “ensure that your data will be understood and interpreted by any user.”[18] This documentation can pertain to project-specific definitions; decision-making processes; frameworks related to roles, responsibilities, and permissions; privacy and risk considerations, #legal mechanisms connected to the data (e.g., licenses, data sharing agreements, etc.), and necessary context about the project’s provenance or history. Different documentation components can be public or private depending on the sensitivity of the information.

A shared definition of data governance and thorough data governance documentation become especially significant when it comes to communicating with new collaborators about your data governance practices. It can be difficult to involve many different actors in governance, but documentation can help determine entry points for actors with different capacities and interests. It can also be useful internally as a method for building institutional knowledge, especially when projects face turbulent political environments or if funding lapses.

Module Two: Opening up data governance engagement pathways

The second module explored how to best engage with the priority community actors identified in the first module, focusing on their ideal roles, and how CoAct could communicate about data governance with them and collaborate on aspects of QPR’s data governance. For this session, we focused on the community library staff. Because they had previously been workshop organizers with CoAct, they had experience being users of the data platform and could build the skills and capacity to fill a more intermediary role such as data curators or community liaisons.

We had two guiding questions for this module:

- What training, agreements, or guides might help engage those users (community library staff)?

- What policies, tools, or data practices are needed to better integrate those users into data governance processes?

As community liaisons, library staff must be able to understand the difference between open and closed data, and to explain these differences to others, such as members of the public who attend workshops. As data curators, CoAct wanted community library staff to be able to review submissions to the QPR data platform, publish community-submitted data that had been vetted as non-sensitive data, and archive the more sensitive data into a password protected repository. For this role, CoAct delineated a broader data governance training that would build capacity around data sensitivities and aggregation, and provide examples around disclosures. They also highlighted that it would be useful for library staff to grasp the technical aspects of the platform that enabled data sharing to support their understanding of the purpose and mechanics of the quality assurance and control tasks.

We also discussed how to incentivize and tailor this learning for the community library staff. For example, building up basic data governance and literacy skills would have benefits beyond this project in the staffs’ personal and professional lives. Especially in today’s data-saturated society, having an understanding of data privacy and security could support people in making more informed decisions about their own personal, health, or financial data. Adapting this learning for the community library staff brought up several key questions for the CoAct team to work through: How could they explain things in a simple and appealing way? How could they incorporate rewards or progress indicators within the platform? And how could they communicate the purpose or the benefits of the process?

We came to the conclusion that CoAct could take a few different next steps to build out their collaboration with the community library staff and other community actors in the future. First, they could pilot a data curator training program with a small number of testers from the community library staff and include modules on open and closed data and basic data security training. They could also develop a checklist that detailed the workflow for reviewing data submissions. Alongside this development, they should document clear roles for each collaborator and project member, with special focus on the data curator role.

Takeaway 9: Truly participatory data governance requires deep understanding of each collaborator or actor, including their values, incentives, and capacity.

Data governance can seem like a difficult or nebulous concept—many approach the topic unsure of its meaning or purpose, or assuming data science understanding is needed to interact with its practices or frameworks. This is why it’s critical to have clearly defined pathways or roles for community actors to fit into; creating those pathways and roles requires a thorough understanding of how a community actor may or may not want to participate. Creating user personas or interviewing interested actors to understand their values, incentives, and capacity can ensure that engagement can be productive for both the project and community actors. Ultimately, expanding governance to community actors allows for greater representation in decision-making, and can create greater wells of interest and awareness outside of the main project team.

Resources created, next steps, and outcomes

After the workshop, we created a synthesis of next steps for CoAct to consider. With each community partner, we held check-ins at the three and six month marks after our official collaboration ended. In these meetings, the CENIT team shared their progress in creating a project-wide governance document that provides clear definitions of the data, their existing governance and decision-making processes, and issues to be resolved. They also shared that they have held a workshop with FARN to discuss this document, and both reported that they are still in discussions to collaboratively finalize it.

CoAct defines citizen social science in this way: “Citizen social science combines equal collaboration between citizen groups (co-researchers) that are sharing a social concern and academic researchers. Such an approach enables [us] to address pressing social issues from the bottom up, embedded in their social contexts, with robust research methods.” Access more on their approaches and practices here. ↩︎

https://www.google.com/url?q=https://coactproject.eu/news/water-quality-and-citizen-social-science/&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1743527976450112&usg=AOvVaw2ChTP1CNZq4y8E4kKOAwC6 ↩︎

https://coactproject.eu/news/water-quality-and-citizen-social-science/ ↩︎

https://globalpressjournal.com/americas/argentina/plagued-health-issues-residents-near-dirty-river-argentina-options/ ↩︎

https://www.univision.com/noticias/citylab-medio-ambiente/los-residentes-pobres-de-buenos-aires-conviven-con-uno-de-los-rios-mas-contaminados-del-mundo ↩︎

https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/articles/entry/banks-latin-america-most-polluted-waterways ↩︎

https://www.webuildvalue.com/en/stories-behind-projects/riachuelo-cleaning-up-argentina-s-most-polluted-river.html ↩︎

https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/there-still-hope-latin-americas-most-toxic-river ↩︎

https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/there-still-hope-latin-americas-most-toxic-river ↩︎

https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/there-still-hope-latin-americas-most-toxic-river ↩︎

https://www.eldiarioar.com/opinion/decision-corte-necesita-coraje-institucional-riachuelo_1_11775272.html ↩︎

https://www.eldiarioar.com/opinion/decision-corte-necesita-coraje-institucional-riachuelo_1_11775272.html ↩︎

CC-BY-SA is a license created by Creative Commons, enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. More on this license can be found here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/. ↩︎

FARN has many areas of action and study, which are organized in different departments, such as environmental policy, climate policy, biodiversity, research, legal affairs, legal advice clinic, press, and communication. The department of legal affairs is responsible for the CoAct project, but there have also been interactions between the project and the biodiversity department, as well as with the press and communications department. ↩︎

We will use the term “data governance framework” in this instance to indicate the set of rules, processes, and practices that a particular organization or set of stewards utilize regarding the relational and technical aspects of their data governance. ↩︎

https://data.library.arizona.edu/data-management/best-practices/data-documentation-readme-metadata ↩︎