CHARRS

Located in Atlanta, Georgia, Community Health Aligning Revitalization Resilience & Sustainability (CHARRS) is an organization that examines the social determinants of health and their impact on African American and other underserved communities in order to implement solutions to the inequities and injustices associated with them. CHAARS is currently collecting hyper-local #airquality data using reference and handheld monitors. The organization is developing and involved with multiple projects, including PROJECT REMOVE and AQEarth, across which they seek to expand data accessibility to EJ nonprofits and community members. CHARRS invited Dr. Na’Taki Osbourne-Jelks from the West Atlanta Watershed Alliance (WAWA) to participate in our collaboration. Dr. Osbourne-Jelks is “working to improve the quality of life within the West Atlanta Watershed by protecting, preserving and restoring the community’s natural resources."[1] WAWA represents African American neighborhoods in West Atlanta that are most inundated with environmental stressors and least represented at environmental decision-making tables.

Environmental Justice in North and Southwest Atlanta

CHARRS and WAWA work largely in neighborhoods in West Atlanta, made up mostly of African Americans who have lived in this area due to histories of racial and economic segregation—in the 1950s and 60s, redlining and the placement of Interstate 20 solidified segregation, and thus, unequal opportunity and adverse living conditions.[2] Communities in this area have been battling environmental injustices since as early as 1900 when activists opposed the actions of a furnace operator who was dumping waste into Proctor Creek.[3] Today, these communities are still actively fighting for cleaner water, air, and land. A 2012 report from GreenLaw determined that a section of West Atlanta ranked highest among other pollution hotspots in Metro Atlanta, largely because it has historically contained the largest warehousing and transportation building concentration east of the Mississippi River.[4] The Chattahoochee River, the lifeblood of the city and region, runs less than a mile from many of the resulting pollution sources. Both inactive and active industrial sites across West Atlanta contribute to the release of toxic chemicals into the air and waterways, and leaching into the soil.

Another threat to Atlanta waterways comes from outdated and problem-prone sewage infrastructure. In a decades-long ordeal, overflow events occurred after heavy rainfall when the volume of water flowing through the pipes (carrying sewage, rainwater drainage, and industrial wastewater) exceeds the wastewater treatment plant capacity.[5] Some excess water must be diverted to nearby waterways or out of manholes into city streets, contaminating them with untreated or partially treated sewage. Climate change exacerbates this issue with more frequent, unpredictable, and extreme rainfall events. Activists have been organizing to address this kind of contamination since the 1990s. Today, organizations including CHARRS and WAWA are working to engage residents from these communities on these issues while also supplying them with the data and tools to elevate their voices and seek self-determined outcomes for environmental, policy, and systems change.[6]

CHARRS collects...

CHARRS collects, uses, and manages many different types of data, including:

- Indoor radon gas levels in residences (as part of Project REMOVE)

- Air quality data, including hyperlocal air monitoring data of 6 criteria pollutants (CO, PM2.5, PM1, O3, NO, NO2) (as part of AQEarth)

- Black carbon data (in collaboration with Dr. Christina Fuller from the University of Georgia)

- Survey data from West Atlanta residents who attended meetings (as part of Project REMOVE and AQEarth)

- Data about people who bring items to repair and what is being repaired (alongside the Atlanta Repair Cafe)

Challenges

CHARRS has several challenges surrounding the usage, sharing, and general governance of its data. The data CHARRS collects are safely secured, stored in CSV and XLS files, but currently closed to the public, and the datasets lack deeper analysis and context. CHARRS wants to be able to provide access to aspects of the data while ensuring that the data doesn’t identify specific people or locations. CHARRS has strong relationships with local universities and other EJ organizations in the region, so it wants to safely share data with relevant collaborators, but lacks the data sharing and use agreements that might ease this sharing. During our collaboration, CHARRS had one full-time employee, thus had limited capacity to develop these resources.

The #interoperability of its data (or lack thereof) poses another challenge for CHARRS. CHARRS has quantitative data from the AQEarth project and are interested in finding ways to tell a more representative narrative of pollution and its impacts. CHARRS and WAWA also noted that they want to use the data from government sources like the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) PLACES population health data and the EPA’s Criteria Pollutant data to perform localized analysis alongside their own collected data on air and water quality. However, it is difficult to analyze these datasets together alongside CHARRS’s collected data because of the difficulty matching up the geographic scopes, or differences in units of measurement. CHARRS’s longer-term goal is to build a platform where data can be uploaded, managed, and shared among different EJ organizations, the public in Atlanta, and, eventually, all of Georgia.

Current governance and management

As mentioned above, the data from each of CHARRS’s collaborations (AQEarth and Project REMOVE) is currently not public. There are slightly different governance and #management structures for each project, since each includes different collaborators. For example, with Project REMOVE, which collects radon data, the metadata comes to CHARRS ready to use and is publicly shared. This data is stored by Georgia State University and is under Dr. Dajun Dai’s control. AQEarth datasets are stored on Montrose Environmental’s servers, on their Sensible Environmental Data Platform, and are not currently open to the public. Decisions about this data are made collaboratively by the respective project teams, and CHARRS is interested in understanding what shared data ownership and preservation could look like over time.

Goals

With CHARRS, we collectively delineated three central targets to address in the workshop:

- Establish elements of a future data governance framework for data stored in a central repository,

- Build data governance skills to support intentional sharing, and

- Develop a list of data science and management questions to inform how CHARRS hires researchers and writes grants.

These modules largely focused on the data that CHARRS currently has, but also provided space to workshop potential future governance for a platform that is collaboratively managed by (or at least sourced from and used by) the broader community of EJ-focused organizations in Georgia. CHARRS recognized that it would be useful to understand how to approach questions of data governance and stewardship before a technical tool was developed.

In the workshop

We designed the workshop to cover three modules: 1) future sharing and data frameworks, 2) a data sharing agreement building exercise, and 3) data science and management question prioritization and preparation. We had a three-hour virtual workshop to run through these modules with Gwen Smith of CHARRS and Na’Taki Osbourne Jelks of WAWA.

Module One: Future sharing

The first module identified some possible design features of a central repository that would enable CHARRS to share and co-manage data with other regional EJ organizations. Through facilitated brainstorming exercises, we identified the potential types of data, stakeholders, roles and permissions, and technical features that could support its preferred sharing methods and governance approaches.

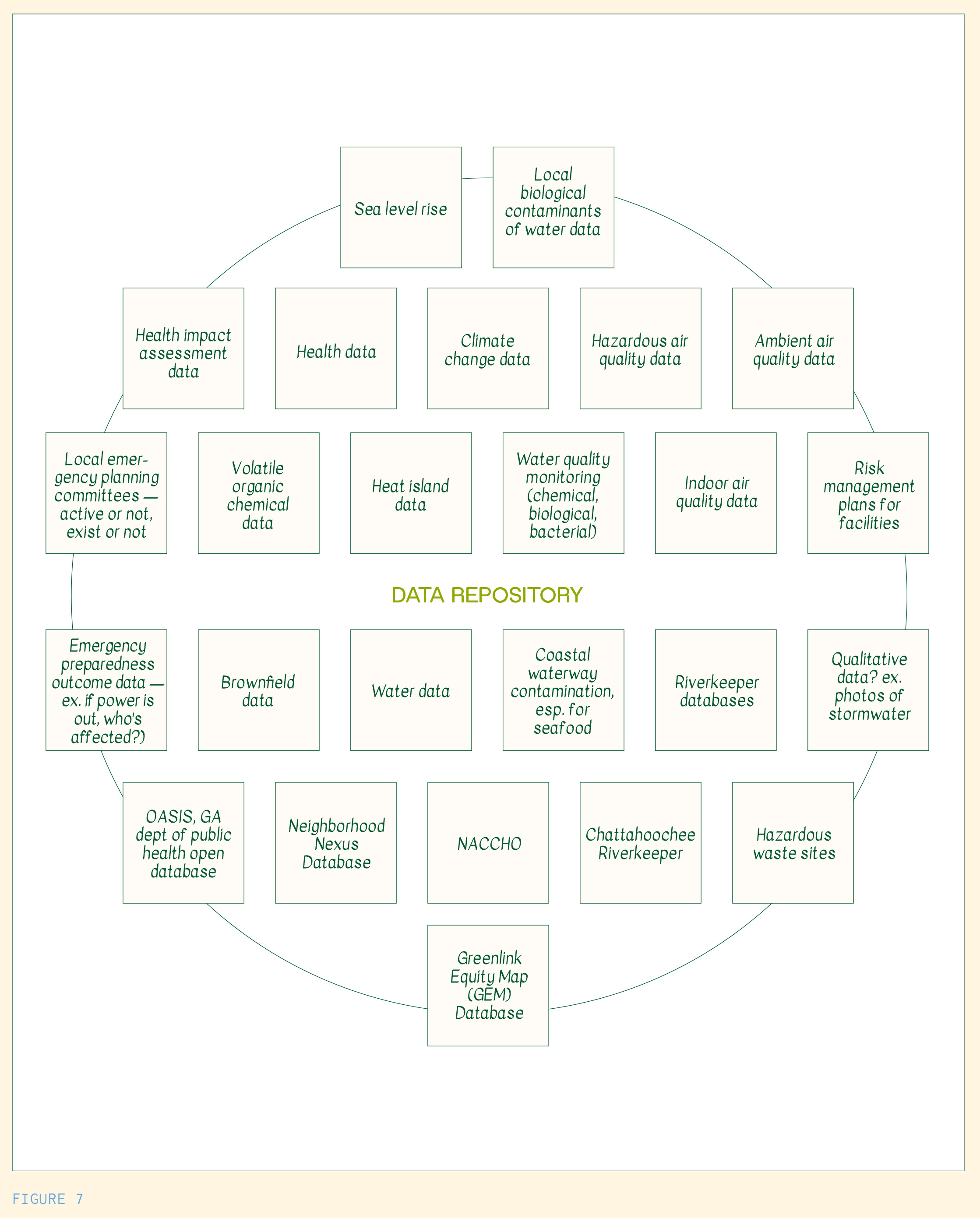

The potential data types included data both currently managed by CHARRS and WAWA, as well as more expansive types of climate, environmental, and health data, including brownfield data,[7] heat island data, and information about local emergency and risk planning. They are interested in understanding environmental and health issues holistically, and these additional datasets would support further analysis and programming. See a full list of data types below in Figure 7.

Potential stakeholders included state EJ groups, students enrolled in primary and secondary education, Atlanta city councilmembers, community residents, and state elected officials. Stakeholder roles and permissions would depend on 1) what they would want to use data for, 2) what data they would contribute, and 3) what level of data literacy and capacity for data management they had. Our conversations around these questions made explicit some opportunities and limitations for certain groups, and also built an understanding of what types of data could be shared—and how—within this system, i.e., who would get access to all of the data, a limited portion of the data, or data products.

Through the module, we made note of particular design features that would not only accommodate the data types, stakeholders, and roles and responsibilities identified, but also respond to existing challenges in current data needs and management capacities. The following table lays out both these challenges and how specific design considerations could be implemented to address them.

| Challenge | Suggested design feature for future system |

|---|---|

| State and public data is difficult to access and understand; it can be especially difficult to “match” this data with CHARRS’s data. | If collaborators want to add data, contributors must agree to use specific data formats to facilitate data matching and integration. |

| It is currently difficult to analyze both qualitative and quantitative data side by side. |

A future data system must have the ability to hold multiple data types, including photos. |

| Users would need different levels of access to protect community members’ privacy. |

Sensitive data would require access codes, and some data that includes PII would not be available to anyone outside of the project team. Some users would only be able to access data products and not raw data. A licensing scheme could also be established to allow for specific types of access or use. |

| There is data categorized by county and census tracts, but less so for census block groups.[8] CHARRS and WAWA need finer-grained data than what usually exists, and WAWA works on a watershed level that crosses over jurisdictional lines. | A future data system must be location-centric, and include #mapping abilities with different layers that allow for analysis at the neighborhood scale. |

Takeaway 4: The technical design of a data system can, and should, reflect data users’ needs to unlock the value of the data.

CHARRS and WAWA have worked hard to collect hyperlocal data that is critical to answering environmental and health questions in their community, yet their current digital tools don’t allow them to use the data in ways they would like. Data governance is a continuous balance between the roles that people play, the actions they take, the processes they create and participate in, and the technology that supports the data throughout its lifecycle. Technical design features can either hamper effective use or enable greater control and collaboration. While it is hard to prescribe a pre-made system of governance that will cater to each community’s social and technical needs, there are processes and resources that can support a community's understanding and utilization of data governance practices and frameworks. As a data steward, facilitating conversations to understand user priorities, and identifying how those priorities translate into technical design features for digital infrastructure, can address some of these challenges. Other strategies are available and outlined in About the Plays.

Takeaway 5: Data ownership, in practice, has material requirements; it requires somewhere to house the data and someone to maintain it.

This takeaway is essentially a direct quote from one of the participants in the first module, and its insight is clear-cut: data ownership and community control require resources and capacity to work properly. The costs associated with building and maintaining databases or other digital infrastructures, creating #dataanalysis tools, and enforcing data standards are often out of reach for small, community-based organizations, and require consistent, operational fundraising to maintain. It sounds simple to “share data,” but there are high costs associated with the technical tools and human resources needed to meaningfully govern data.

Module Two: Building data sharing agreements

At the time of the workshop, CHARRS wanted to know how to responsibly and effectively share their collected data with community members, researchers, and state governments, but did not have infrastructure set up to support this. We ran through a scenario with a potential data sharing partner: a professor at Emory University who wanted to use reference monitor air quality data. We asked the following questions to develop a data sharing agreement:

- What are the main considerations for sharing with this recipient?

- Who are the parties to the agreement?

- What specific data items will be shared?

- Are there restrictions of use? What are they?

- What is the time period of access?

- How will CHARRS maintain access to the data or end access to the data?

- How will the recipient communicate how the data is being used during the sharing period?

These considerations are meant to both protect and acknowledge the work that CHARRS and others have done to collect and steward this data. CHARRS recognizes the potential for data #extractivism, where researchers or commercial entities can “extract resources like #knowledge, wisdom and stories in the form of data from communities.”[9] This is especially prevalent in communities facing environmental injustice, and data sharing agreements can be a strategy to bolster relational accountability, and to avoid data sharing partnerships that are exploitative and bring little positive impact to the community whose data is being utilized.

The main considerations that stemmed from this discussion were that CHARRS wanted to make sure that they received authorship credit in resulting publications and articulated how they would like to be attributed within those publications. In cases when a researcher planned to publish something using this data, CHARRS also wanted to include parameters allowing them to review drafts prior to publication to make sure sensitive data wouldn’t be released. Along these lines, CHARRS was also concerned with how the data might be used. To account for this last point, we suggested that they develop a set of pre-approved purposes or use Creative Commons noncommercial licenses so that the data couldn’t be used for commercial purposes.

Throughout this exercise, we emphasized that data sharing agreements are like any other contract—the terms are up to the parties—and so we encouraged CHARRS and WAWA to be explicit about what they wanted in the agreement. For the restrictions of use, CHARRS suggested that potential users should take a data ethics training and register as a user within a future platform. This would enable CHARRS to more easily track which users have downloaded specific datasets, and when those downloads happened. CHARRS also stipulated that partnering organizations notify CHARRS if the main point of contact changed, and provide an emergency contact or access option. This consideration is critical, as project teams representing research institutions can shift based on personnel changes or funding.

For a more detailed exploration of data sharing considerations, see our worksheet: Data Use and Sharing Agreement Questions and the accompanying data sharing how-to guide: The Data We Own - A How-To Guide for Environmental Data Sharing.

Takeaway 6: Data sharing agreements are contracts. They don't build relationships, but can support existing relationships.

Data sharing agreements are essential #legal tools that community environmental data holders can utilize to 1) share their data safely and 2) get what they need from the interaction while providing what a collaborator is requesting. Still, they are simply one aspect of a larger relationship or partnership. There are often power asymmetries between two data-sharing parties—such as community-based organizations and university-affiliated researchers—that can prompt specific needs and restrictions from both parties, as with any contract. Before creating this contract, there is usually a process of communicating these needs, restrictions, and shared goals. This communication is an essential piece of relationship building, especially for community environmental data users and holders, who are often faced with large power asymmetries and are often situated in histories of data misuse and extractivism.

Synthesis and closing

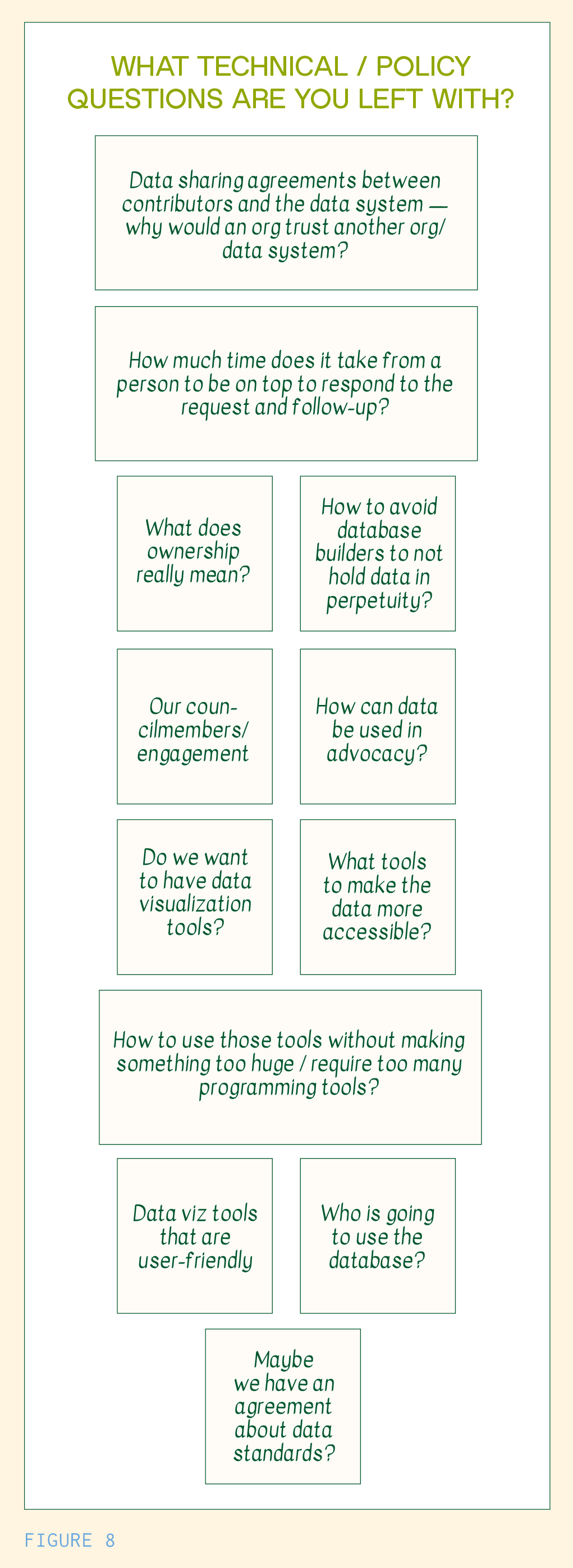

As we closed the workshop, CHARRS had many technical data science management questions that we couldn’t answer in this session alone. We generated a list of these questions (see below, Figure 8), many of which other communities in this collaboration had asked, as well. Some notable themes that came up include how to create appropriately scoped data analysis and visualization tools, what kind of agreements or policies can ensure data ownership, and how to build digital infrastructures and governance systems that can adapt to changing conditions and secure data in perpetuity.

Resources created, next steps, and outcomes

After the workshop, we created a synthesis of next steps for CHARRS to consider and a worksheet of questions and considerations around data sharing. This worksheet included considerations about data owners’ roles and responsibilities, a table with potential scenarios around who could use what and how they could use it, and other conditions CHARRS could place in a data use agreement or attach to data and data products.

This worksheet is available in our Tools and Templates folder, see Data Use and Sharing Agreement Questions.

After the official collaboration culminated, CHARRS, in partnership with OEDP, submitted an application for the EPA’s Community Change grant program, and integrated data governance workshops with the broader community into the application. With each community partner, we held check-ins at the three and six month marks after our official collaboration ended. In our check-in meetings, Gwen Smith reported that she had used the data sharing guidance derived from our workshops to support decision making when approached by a researcher who was interested in applying for a grant regarding local air quality monitoring.

https://scienceforgeorgia.org/knowledge-base1/a-history-of-environmental-justice-in-georgia/ ↩︎

https://scienceforgeorgia.org/knowledge-base1/a-history-of-environmental-justice-in-georgia/ ↩︎

https://scienceforgeorgia.org/knowledge-base1/a-history-of-environmental-justice-in-georgia/ ↩︎

https://chattahoochee.org/case-study/wastewater-chronic-sewage-spills-by-city-of-atlanta/ ↩︎

https://villa-albertine.org/va/magazine/atlanta-reflections-on-beholding-protecting-and-dismantling/ ↩︎

Brownfields are “underutilized properties where reuse is hindered by the actual or suspected presence of pollution.” See more here. ↩︎

The US Census Bureau reports data in differing units, including counties and census tracts. Census tracts are “statistical subdivisions of a county that aim to have roughly 4,000 inhabitants,” and block groups are a subdivision of a census tract, usually containing between 250 and 550 housing units. See more on these distinctions here. ↩︎

https://commonslibrary.org/beyond-extractivism-in-research-with-communities-and-movements/ ↩︎